2014-2015 VOLVO OCEAN RACE WITH TEAM ALVIMEDICA

Existing as one of the crew and a part of the team, the primary task of the onboard reporter is simple enough: capture the highs and lows of a nine-month 40,000 mile race around the world. It's your job to build the characters and capture the grind through whatever medium best suits the story. A minimum daily requirement of 5-8 photos, one 3-5 minute edited video, and a 300-plus word blog keeps you busy on the creative side for almost 150 days of sailing, while onboard responsibilities to the team entail making water, preparing all of the food and onboard nutrition, and keeping a constantly submerged boat [relatively] free of water in the bilge. Cussing like a sailor, optional and occasional.

DAILY BOATFEEDS

DAILY BLOG EXCERPTS

“All of the comparison to past races, to the last race in particular, of course it makes you think. Yesterday, in the remnants of the night’s nastiness, my new boots—notoriously slippery with fresh rubber and chemicals on the sole—failed me. As I was coming down the hatch, one hand on my camera the other on the strap hanging from the ceiling, my feet lost their grip. All of my weight on my shoulder, it dislocated (as it does too often), I let go, and landed awash in the wet bilge. Camera saved, I put my shoulder back in its place and then started bailing that bilge and the rest of the boat for the next hour. Never told anyone. Not that I would ever feel sorry for myself, but I chose to come back here for "more" and at that moment I started to wonder why. Yesterday passed just fine with moderate soreness but last night’s sunset was as good as ever. Dave quietly acknowledged that this race gives you “just enough of them to keep bringing you back.” As I rattled off some 300-pictures in 20 minutes of intense orange sunset-fed obsession, I looked around and realized I was back doing something that made me really happy; why would I ever want to be anywhere else? The friends you make, the ways you challenge yourself—we all give up a lot to be here—sometimes it’s a shoulder, other times a family. But for most of us it’s ultimately worth it in the end. I left Alicante ready for weeks of sailing to Cape Town, but I think the reality of being a part of this great Race again is finally setting in." October 15, 2014. Leg 1, Day 4

“It's like flipping a switch. OFF to ON in so much as an instant, the strong westerlies of the South Atlantic have arrived and it never ceases to amaze me how quickly life onboard can change. One minute I'm enjoying a nice nap, comfortable in the sleeping bag. Things are mellow. Tranquillo, as Charlie says. Dreaming about home, maybe a steak in Cape Town. Something wakes me and I open my eyes to a very different, very alarming scene. My eyes slowly adjust to the darkness, the only available light coming from red headlamps of guys around me trying to do the same. I reach for my headlamp and fumble with the buttons. It's loud, a deep rumble like distant thunder. You can actually hear the speed, feel the speed, from inside where you stand. Like accelerating in a sports car with your eyes closed, offroad, and in the rain. As the boat careens through the night like an out of control freight train, carving a trench through the ocean and obliterating every bit of water in its way, people on deck are yelling. Bags are flying, water's shooting through the hatch and all I and everyone else just rising from their bunks are trying to do is get to our feet. Now the kettle’s tumbled to leeward because the boat is nearly on its side. I hear it klank loudly, twice, and then it lands in the rapidly filling bilge with an unmistakable splash—a noise so annoying because I know I'm gonna have to go down there and get it. Like, now. For a brief moment I actually remember my dream. Mountains, snow, and a philly cheesesteak in front of a hockey game at Cuddy’s in Jackson, Wyoming. A crazy thing to be thinking of, I think." October 31, 2014. Leg 1, Day 20

“We'll eventually pass within 150 miles of Pakistan and in sight of Iran, then through the Straits of Hormuz—a hotly contested stretch of water where our progress will be solely dependent on the wind, or absence of it. I'd be lying if I said that didn’t worry me a little. The truth is that no matter how safe somebody tells you it may be, pirates or terrorists don’t abide by rules and they don’t have a playbook; they are the definition of unpredictable. One day they may wake up and do things differently than they did the day before, and no amount of consulting or assurance from professionals can challenge that reality. Though we’re about halfway through this leg, this second half is full of risk—real risk—and you can be sure it’s on our minds. We put a lot of faith in the race organizers and their decision to send us all the way to Abu Dhabi—we have to. And of course, with just 5 knots of wind and little else to do but talk, maybe we’re just winding ourselves up. But as our progress northwest continues this is something that will remain on our minds, all the way through the Arabian Sea." December 4, 2014. Leg 2, Day 15

“Little love, these Doldrums clouds. But they continue to push us somewhere and if you were to ask us yesterday, somewhere—anywhere—is better than nowhere, and we were going nowhere for a long time. A couple of the guys went swimming but otherwise we just sat around looking at the windless horizon, devoid of detail in every direction. We all knew it would take a long time to get to Abu Dhabi, I think we mostly agreed it was going to be about 30 days. We packed for it, we’ve talked about it, and when you set your expectations like that, a 30-day leg really isn’t a problem. It’s a long time to spend on a boat like this but we’re prepared to do it. I think the heat is becoming something different though. The heat may break us. It is so stinking hot. And you can't hide from it. On deck there is only shadow for a short time, and down below it’s maybe worse. A black boat full of people, electronics, few air passages, and an occasionally running generator, it all adds up to extreme levels of discomfort that prove distracting in every way. You think about it all the time. A consequence of this lack of activity though is the new “sunset gym.” Seb and Housty’s watch occupies the transition from day to night and they’ve gotten into the habit of using the last hour of cooler temps to keep themselves in shape with pushups and various simple exercises. It’s caught on and anybody awake at the time tends to join in. Staying fit out here with the lack of sleep, malnutrition, and limited real estate for movement can be tough, but what little effort we can make will go a long way towards keeping us sharp—physically and mentally. And in looking at the slow forecast for the remaining miles, endurance may prove paramount." December 7, 2014. Leg 2, Day 18

“It was hours of pure chaos under the moonlit shadow of Vietnam. With the actual coastline and its many lights to one side, and an armada of fishing boats and nets to the other, it was nearly impossible to distinguish between fleet and shore were it not for the varied elevations of lights on land. There were lights everywhere. Hundreds of little boats and even unlit, overturned saucers with only an oarsmen and a headlamp, drifting in the darkness. We could just have easily run someone over as we could have hooked a net, anchor, or both. The margin for error was so ridiculously small. And making things worse was the lack of consistency; there was no rhyme or reason to any of it. Blinking lights, solid lights, white, yellow, blue, red—it made no sense and turned the coastal transit into total guesswork. Charlie claims it was “the most intense night of sailing in my life.” Duh. Our midnight passage through Singapore Strait, the busiest shipping port in the world still just a few nights earlier, that says a lot about our last week out here... And once through the mess and back offshore, back into a watch system after sunrise, the boat went eerily quiet. There was no talking down below, only sleeping. Tired from another all-nighter but wanting to get an early start to the editing, I sat down at my computer with a coffee only to wake up just before I needed to make lunch, hunched over the keyboard. It has been an exhausting end to this leg, an exhausting leg in general, and the 300 miles that now stand between us and the finish in China may prove most exhausting of it all. Second through fifth place are back in sight of each other and with a few short days of straight-line sailing left nobody is going to give up an inch." January 25, 2015. Leg 3, Day 22

“Last night was arguably one of the most impressive I have ever spent on a boat. Quietly slicing through the calm sea the bioluminescence was on fire. It was like the water was plugged in, a Halogen wake. Everywhere you looked there was sea life in motion, explosions of neon blue: a flying fish walking along the surface, a blossoming bloom of squid or fish, visible far beneath the surface, or dolphins playing under the bow, their shades and stripes aglow even to the naked eye with such detail, and a torpedo-trail of blue bubbles in their wake. It looked fake, like some special effects scene from a big-budget Hollywood film. No one had seen anything like it, not even close, and I was, according to Nick, “peaking,” boyishly excited to finally catch the night lights on camera (Phosphorescent activity is usually far too faint for the film sensors of a camera). It was unreal. The stars got their time to shine, too, so bright you could see the reflections on the water at your feet. And then it was time for the Omani mountains to the south at sunrise. Large, barren, and every bit as impressive." December 12, 2014. Leg 2, Day 23

“Learning to make better decisions is a riddle slowly solved—it’s a matter of time and conviction, and understanding that you can’t always get it right. But how do you get faster? It is one of sailing’s oldest mysteries and most intriguing qualities. You can be the smartest boat in the fleet but if you can’t go through the water well it doesn’t much matter. And likewise, blinding speed can hide tactical deficiencies. But there is no sure recipe for speed: it is as much feel as formula, and this is especially true in a one-design class. Over the last few days we’ve isolated our speed needs to the super-light conditions. It’s become one part frustration—there is nothing more painful than watching the competition slowly sail away—and one part education: there is no better place to observe, to learn, and to experiment than when you’re right next to someone who’s going faster than you are. As the saying goes: imitation is the best form of flattery. And we’ve spent a lot of time looking through the binoculars. It is just part of the process and we know that the moment you stop asking questions and looking for ways to improve is the moment you’ve lost the drive to succeed. And this team wants to succeed, badly. We know we’re oh-so-close to putting it all together. As soon as the breeze comes up a bit we can hold our own with the best of them, so it’s a targeted effort to improve in fewer than six knots of wind." January 8, 2015. Leg 3, Day 5

“The shutter kept firing until it stopped, my finger now raised from a rewarding burst of frames on the bow. Housty, spread across three sail bags while we drift in a pool of virtual nothingness, sarcastically asks why I need to take so many pictures? My initial reaction was to reply that I never told him how to trim a sail. Defensive, as usual. On a boat where you’re kind of the exception you spend a lot of time trying to justify your differences. But then I started to explain, and it’s probably the first time any of these guys have taken interest in what goes in to capturing the images they consistently demand for download when we arrive, and it made me think about my job, which is something I don’t often do. I guess I take a picture until the product replicates the way I see it. Most novelists start with an idea; they know the brief before they start writing. Most directors start with a script. I look at a scene and I use the tools available to make it match what I've already seen with my eyes. And no matter how many times a traditionalist may boast about the “olden days,” where 12 exposures of film was all you got, I can fit thousands of photos on my 64 gigabyte SD card and if it takes that many until I get the right one, I plan on using all of them. Sometimes you never find it, and that’s when you can lean on the words a bit more. It's one of this job’s greatest qualities, the combination of mediums. We get to write. We get to film. And we get to photograph. I’m partial to the words and the pictures because it’s my say, my way—I get to tell the story. I don’t like selfies and I don’t film myself so I rely exclusively on the sailors for their own video personalities. But the pictures and the words—those are on me, and I love that kind of control." January 10, 2015. Leg 3, Day 7

“It’s a bad sign when you wake up to TLC and Waterfalls on your iPod. It means you’ve pretty much exhausted every song on the thing, and the only sliver of “new” that was left, your 1998 Summer Jams playlist, is now as old as it’s age. Old, kind of like these conditions. A hopeless episode of the Groundhog Day, as Dave accurately declared during this morning’s identical sunrise. The only thing extreme about life onboard at the moment is the diversity in our stories. It always amazes me how many are left to hear after sixty-plus days of sailing in this race. Lately youth sports have taken hold, stories of our glory days on the pitch, field, court and rink, and you’d almost believe we were all athletes at one stage! The “yarns,” kiwi for tall-tales, usually finish with a fair mandate to “stop talking to the driver,” and we’re reminded that while breaking the monotony is nice, staying sharp is critical. Anyone that’s ever gone offshore for an extended period of time will attest to there being a strong story culture to the routine of passing time, and unfortunately, these past 48 hours have been just the type to make such stories. Will says he’s never seen a windless hole this big, and knowing he’s A) weather obsessed, and B) extremely well traveled, I put credence to his claim. We've seen nothing but our reflection in the glassy waters around us, which gives a false feeling of remoteness to this crazy corner of the Indian Ocean. Ironic, knowing what is in store for us around the corner in the Malacca Straits. Remember that time in the Bay of Bengal, when we were stuck there for like a week? I can already hear its embellishment during becalmed watches of the future. I saw a piece of trash when I went to bed and it was still there when I woke up! But that’s kind of what it feels like, like we may be here forever. Certainly an extreme of windlessness that none of us have really experienced." January 16, 2015. Leg 3, Day 13

“The good news is we only have about 150 miles left in the South China Sea. The bad news is we still have about 150 miles left in the South China Sea. On a discomfort scale of 1 to 10 I’d say we’re firmly pinned at 11. It’s an indescribable feeling of nausea that takes hold within the first 36 hours of a rough leg start, a stomach churn so permanent that it makes you incapable of doing anything, at least not well. Your body needs time to acclimate—time that we didn’t supply it—and whether you throw up or not doesn’t matter; the group universally feels like crap and it lasts until conditions improve. Your bunk is probably the only place you can calm the onslaught but the reality is you can’t ever climb in it. There are sails to change, a boat to drive, meals to cook, or a blog to write. Everyone has things to do and you just have to tough it out and remember that it always gets better…eventually. There’s nothing to do but make sure you’re hanging on to something all the time because you never see half of the waves, especially not when you're down below. And when the bow leaves the water there’s an uncertainty as to just how long it will stay there. Sometimes it seems like forever as you hang, suspended midair, for a second or two. But the slamming has eased up for now, a window I’m using to finally put finger to keyboard, and the sun has poked its head out of the clouds. Despite the deeply unsettled feeling in my stomach and the fact I haven’t been able to eat a thing since yesterday’s lunch—it’s easy to see we’re all really happy to be back out here as a team, in the mix and racing towards New Zealand." February 10, 2015. Leg 4, Day 2

“We talk a lot about clouds, about being on the right side of them and about being ready for everything and anything. Conditions around clouds are always changing but we can’t be swapping sails to accommodate shifting winds every twenty minutes. Sail changes are slow and we just don’t have the manpower to sustain that kind of workload. Instead we play the law of averages and choose a sail that’s more often right than wrong. Enter the “crossover,” a word you’ll hear time and time again on a day like today. We have to weigh the strengths of a sail against its weaknesses, and if the strengths come out ahead you stick with it until they no longer do. It's an imperfect science. In our current 9-12 knots of wind the Fractional Code-0 is the right sail, most of the time. The larger Masthead Code-0 starts to feel too powerful at 10 knots, so 10 knots is the “crossover” between those two sails. But we can’t sail as high with the Fractional as we can with the Masthead, and we'd rather be high, so we’d rather be on the Masthead, but given the abundant clouds and the tendency for periods of stronger winds, the smaller Fractional is a safer, more versatile setup and so we’re choosing to live on that side of the crossover, for the time being. If the wind trends below 10 knots however, we may move to the Masthead, which is still on the crossover, but on the better performing, riskier, other side of it. We spend a lot of time pouring over data trying to identify these vital crossovers—when one sail becomes noticeably better than another—but in a part of the world so unpredictable it’s a conversation that never ends. Being mostly right and more importantly, staying adaptable, is more important than being perfect and fast all the time. You work the trends, keep your eye on the horizon for trouble, and always question your setup. And right on queue, the call for the Masthead just came through the hatch. Everybody on deck!" February 19, 2015. Leg 4, Day 11

“I unclipped my spraytop from the gear rack to find a pair of fleece-lined dishwashing gloves stuffed in the chest pocket. I knew they weren’t mine. Timing has never really been my thing, and at the exact moment I pulled the gloves out Stu stumbles through the hatch. “Peaking a bit early ay?” It’s precisely the tough Kiwi humor I came to appreciate during the last race. Part stab and part honesty, there’s nothing you can say back to guys like Stu—he’s been around the Horn six or seven times and if he says you’re peaking early, you’re peaking early. Knowing there was no point in explaining they weren’t mine I said “probably," returned the grin, and went looking for their owner. “Nick—here are your gloves. And Stu thinks you’re peaking early.” Nick and I have adjacent hooks on the rack and I’m always finding his things in my gear, and the point of this story is that it’s getting cold and wet and everyone’s starting to add layers as we dive south. Stu raises a veteran point: ALWAYS have something more in the bag to add. A wise man in the mountains once told me that if you’re cold it means one of two things: you’re either really poor or really stupid. And seeing as we have a container full of warm clothing to pull from before we leave, it’s wise to avoid being stupid, particularly when packing for the Southern Ocean. Nick was just testing his gloves. Like Dave is testing his dry-suit. Like I’m testing my camera housing. Because the last few days of wet weather have been a small preview of our next few weeks, only they will be much wetter and much colder. And it’s best to find faults now before repairing them is no longer an option. Nick loves his gloves and he’ll probably wear them at night now. Dave has been trimming his neck seal because he still goes purple in the face after an hour in the dry-suit. My waterproof microphone isn’t working well and I need to come up with a fix, and fast. But at least we're dealing with it now, while we can." March 20, 2015. Leg 5, Day 2

“It would appear the Southern Ocean has been saving its best for last. It’s bitterly cold, the water stings your face on contact, you’re drenched, tired, hungry and numb—but you cannot wipe the smile away. It’s like watching a scary movie: you’re uncomfortable and on edge the entire time, but there’s something about it that makes everything so much fun! This is exactly what we expected and furthermore, what we came looking for, and everyone seems to be at their happiest, even in discomfort. A boyish glee emanates from all of the exhausted faces, a deep breath of cold ocean air and a wayward glance towards the towering waves we’re now amongst. It’s easy to understand why this place is so addicting, why for as painful and miserable as it can be and as tough as it is to get here, so many make the sacrifice to return time and time again. Cape Horn is about 160 miles away and we’re clinging to a three-mile lead on the approach. It’s hard to explain how much that means to us, and as someone who’s tasked with doing just that I’m nervous about tomorrow morning. I’m concerned with capturing the experience rather than living in it, and there’s a lot of pressure to document such an achievement for the six guys who have never seen the Horn, and who may never again. But rounding the Horn is not about being first or third or sixth, it’s about completing the passage. It’s about achieving something special as a team, about racing across the Southern Ocean safely, challenging yourself and pushing the limits of those around you. And we will celebrate that when we get there, as a team." March 30, 2015. Leg 5, Day 12

“It’s an unfortunate byproduct of this race, that Cape Horn is reduced in many ways to a waypoint on the course to Brazil. But that’s not to take away from its significance, or in our case the value in representing a massive achievement to getting there the way we have, capping a two-week tear across the Southern Ocean. On one hand we’re programmed to be professional, trained to avert attention to Itajai and Brazil because that is where points are awarded. It’s not necessarily cool to be romantic about a pin on a map, and definitely not cool to be overly excited about leading with another 2,000 miles left on the track. But if there’s one place during this race where we’re allowed to stop and celebrate being part of tradition, celebrate accomplishing something insanely difficult with a group of people you used to hardly know, to celebrate nature, geography, bromance, and simply smile for the purity of just being happy, content with being unique and proud, it was this morning. And we smiled a lot. I stared at Cape Horn not in desperation as I had almost missed it last race, but in admiration. In appreciation. I appreciate so much the opportunity, the privilege to be back down here. I stared in admiration at the men around me, very, very happy to be amongst them. We are individuals that do. Not individuals that talk about doing, but that dream about doing and then make it happen. It’s an amazing team to be a part of with so much enthusiasm, promise and potential. We got here working together in all of the best ways, and arriving first was just a result of that. But there was an unexpected familiarity to it all, like returning to a childhood place I could faintly recall. I looked further—filling in the gaps of my memory like pieces to a puzzle—and the Cape Horn image is more complete than ever. What a special place to stop and think, looking at land’s very end." March 31, 2015. Leg 5, Day 13

“There is nothing funny about this April 1; we’re the fools and the joke’s on us. Survive the Southern Ocean and Cape Horn only to get absolutely destroyed off the coast of Argentina. This will be the most uncomfortable, difficult, and dangerous 24 hours of the leg without question, while we hammer upwind into 35-45 knots and a completely confused sea. Eight hours Will says, eight miserable hours until the front passes over and everything begins to moderate. Eight hours until we can go about repairing bruised bodies and a tired vessel, both of which having already travelled 6,200 miles since Auckland. These conditions make a real mess of the inside of the boat. Things are flying around as we fall of the back of each successive wave. Not that I’ve ever been to space but the way things are soaring, floating mid-air while we fall, it probably feels a lot like being there. And then we crash at the bottom and all of those floating objects crash, too. It's complete chaos. Sleeping bags floating in the bilge to leeward right next to the day bag full of food, upside down. Kind of makes me want to cry. The only thing you can do is put the keel to leeward so the boat heels over more and lands on its side and not its flat bottom. It softens the blow a bit but it’s still scary, the way we’re smashing to Brazil. I have to go and make dinner and I’ll be honest—I’m petrified of the galley right now. I'm trying to figure out where best to clip in my tether as I’ll definitely be wearing a harness. There is nothing more disconcerting than the idea of falling head first all the way to leeward. It’s a long descent with a very hard landing and it would spell certain serious injury. The lengths we go for a decent Roast Lamb... Not sure anyone is in the eating mood anyways." April 1, 2015. Leg 5, Day 15

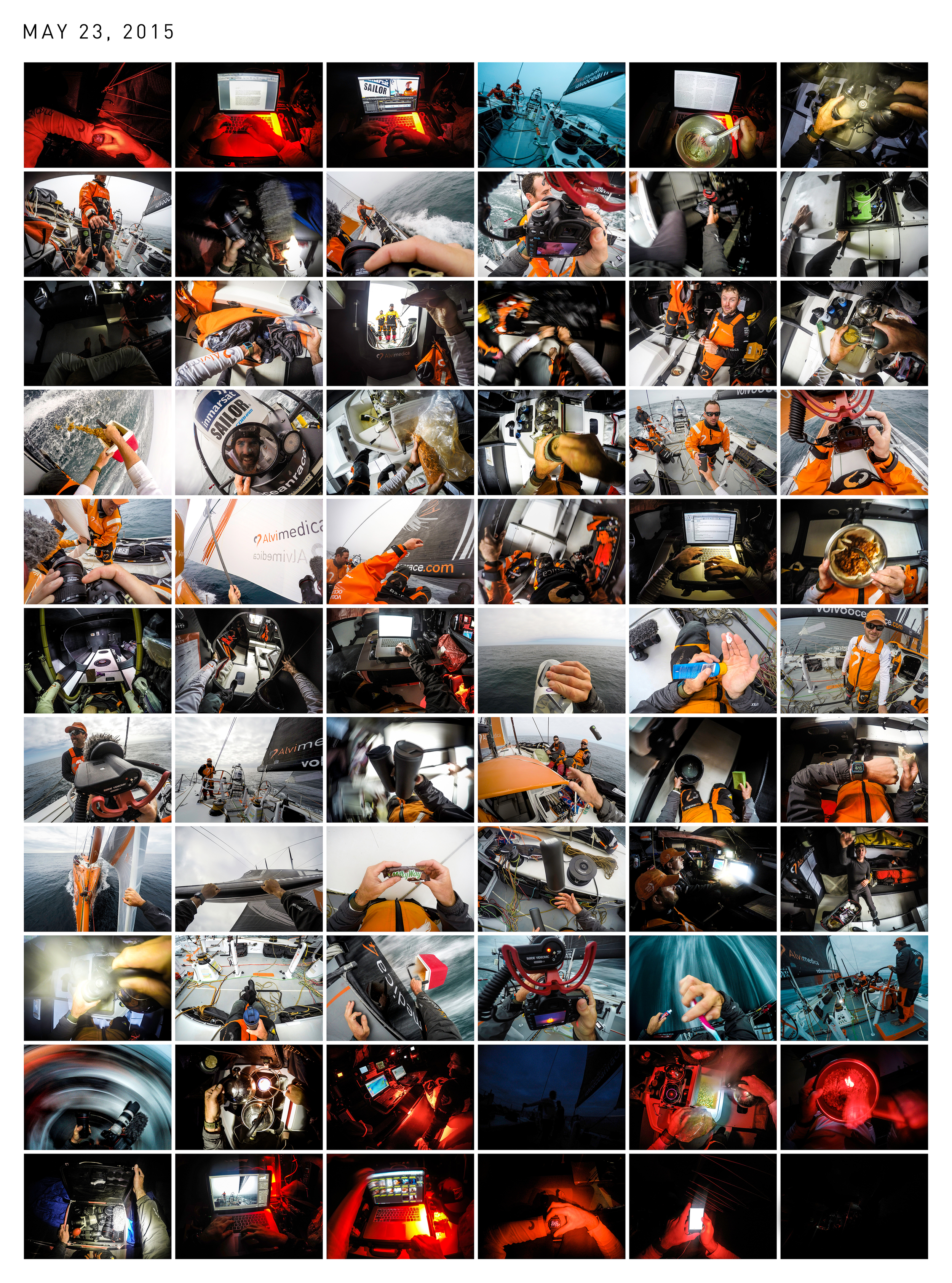

A Day in the Life of Amory Ross: May 23, 2015 (read like a book, starting top-left)